Not "If," But "How"

This is the second in a series about the role of arts advocacy in the age of artificial intelligence. To read the first part, head over here.

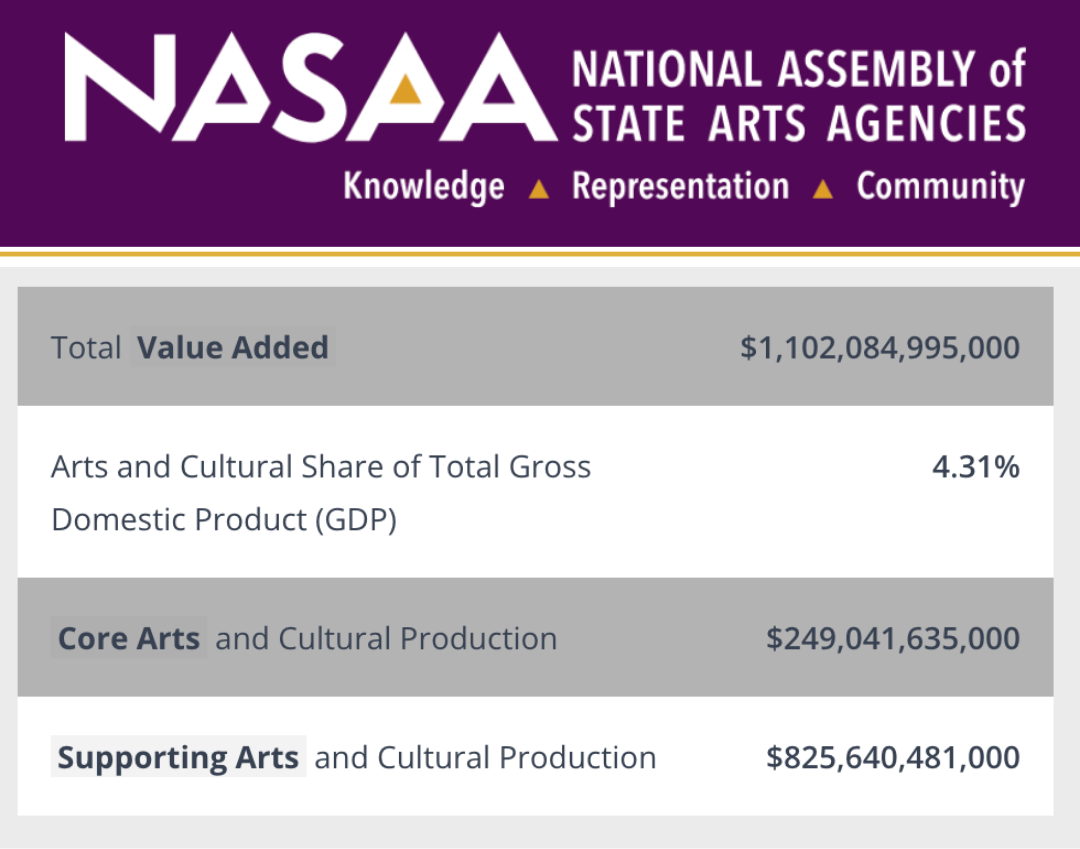

In recent years, we in the arts advocacy space have spent immense amounts of time and resources defending the importance of the arts for their (admittedly robust) contributions to the economy and ability to create jobs. But what will it mean for us when jobs are scarce on the ground, not just for creative workers, but for all workers?

As we stated previously, at this point, it is no longer a question of if artificial intelligence will dramatically affect our lives, but how.

AI looms large in our future world, without a doubt. But what world have we as arts advocates had a hand in creating? When we tout the “almighty GDP” or the number of jobs the arts creates, are we failing to remind our audiences and legislators that arts and culture provide numerous intangible rewards–benefits that improve our lives at the personal level, and ones that are detached from the size of our wallets?

Nothing Stays New Forever

When I officially joined the scene of arts and culture advocacy in 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic that appeared to threaten the very existence of the arts scene in the U.S. entirely, I found myself at the epicenter of the American version of the “new and irreverent” push to see the arts as more than just frivolous leisure activities. In the heat of theaters and museums (and more) closing – many forever – and confronted with a historically socially and fiscally conservative Republican majority and Presidency, it felt to most of us in the space that the winning move was to focus on the economic benefits of the arts.

When the “Save Our Stages” act passed (later the Shuttered Venue Operations Grant), we cheered, high on the triumph of seeing our arguments take root in front of the Senate. We geared up and prepared to tackle the House next, landing the first United States hearing on the creative economy in House of Representatives history. I myself created an over 80-page report outlining “The Power, Peril, and Promise of the Creative Economy” and enthusiastically completed the research for an entire television show based around the concept, Ovation TV’s The Green Room with Nadia Brown.

When COVID-19 vaccinations became available, we rejoiced, confident that audiences would return to arts institutions nationwide as fears of the virus receded.

But then 2021 rolled on, and headlines about theater closures and slashed government funding began to pierce the cotton candy cloud of our optimism. Had our government learned nothing from our advocacy efforts? Were our cultural institutions doomed to wink out of existence one by one, victims of the very market forces we had once championed as the savior of the arts?

The Cost of Accessible Arts & Culture...

You see, Americans could access arts and culture more easily than ever before. From their living rooms to their bus commutes, Americans could tune in to a new Golden Age of television; Netflix gained 27.5 million subscribers in 2021, bringing in an additional $4.6 billion over 2020. Disney+ launched in late 2019, and hit nearly 95 million subscribers by February 2021. YouTube reported 189 million more users at the end of 2021 than the previous year.

And we could hardly claim this was all “low-brow” entertainment, the panacea of the masses. Titles released in 2021 and 2022 include Lupin, Squid Game, The White Lotus, WandaVision, and more.

No, this was art, as even the stodgiest of us had to admit.

And they could do it for the low price of $9/month. An entire year’s worth of streaming cost less than a single Broadway ticket or a pair of concert tickets for date night.

...And the Costs of Everything Else

On top of the cheap price of entertainment, Americans were faced with the need to cut household expenditures more drastically than generations before had needed. While the GDP may have soared in the last three years, for everyday Americans, nearly two-thirds live paycheck-to-paycheck, almost half of them consistently. Prices for consumer goods are 20% higher than pre-pandemic levels, and housing prices are up an astronomical 47%, leaving even basic household goods and shelter out of reach for many Americans.

The arts have come face-to-face with the question of their relevance. We are forced to defend their existence to a world where economic value is the only metric of success – a world we in the arts scene had unwittingly helped to create.

Rethinking Our Approach

In the fruit of our salvation lay the seeds of our destruction.

That’s not to say we were wrong in using whatever tools came to hand in a time of crisis. In the words of groundbreaking cultural economy professors Mark Banks and Justin O’Connor, “[T]he idea that activities such as music, arts and media were economically regenerative and productive (rather than simply a drain on the public purse) and that cultural production could provide ‘real’ jobs and careers (and not just hobbies or distractions)” paved the way for the successes of NIVA, Be An #ArtsHero, and more to create inroads into public funding and attention for the arts never before seen in the U.S. in this generation.

But when we defended the arts solely on economic terms, we accepted the assumption that financial profit was the primary reason for the arts to exist. Everything else resided within the domain of “hobbies and distractions.”

We are at risk of repeating this mistake as we gear up to defend our ecosystem against a new threat: artificial intelligence. While issues of intellectual property, the continued employment of artists, or drawing lines around what is and is not “art” are not negligible concerns, it’s becoming very clear that when we focus on the industrial threat to artists, we risk falling prey to the insidious view that the primary (or even sole) purpose of arts and culture is to make money.

Is that the world we want to live in? As arts advocates, as community members, as parents, as partners, or as human beings?

And if we cannot find other reasons to defend the value of the arts, how will we justify support for the arts if and when AI imperils not just the jobs of artists, or actors, or checkout clerks at our local convenience stores, but all of our jobs?

The Limits of Government

Even if we throw our united support behind attempts at legislating or slowing down the development of AI, those attempts are very likely to fail or come too late for effectiveness. According to MIT, 96% of AI models developed per year are now produced by private industry, with industry models 29 times larger, on average, than those designed by academia.

Appealing to our government to save American arts and culture is also unlikely to work against this new threat.

And it is private industry leaders, not public servants, who are guiding the conversation about AI when it does head to Washington. “[T]the consistently large amounts spent by the big technology companies has allowed them to build up a sophisticated lobbying apparatus that has so far outgunned the efforts of other organizations…Tech companies are able to spend more and thus pay for more experienced lobbyists, who better understand the technical details of their brief better [sic] and have a more extensive network on the Hill,” claims one anonymous D.C. staffer.

[AI] Tech companies are able to spend more and thus pay for more experienced lobbyists, who better understand the technical details of their brief better [sic] and have a more extensive network on the Hill.”

Yes, And...

None of this is to say that utilizing creative economy data is to be avoided. When talking to local voters and community members, I myself still often rely on some of the powerful economic statistics that have come to light in the past handful of years. Watching a constituent have the “light bulb moment” that arts and culture are an economic powerhouse remains gratifying and inspiring, and for legislators who are looking to bolster their community’s budget, explaining the impact that arts investment has on their town or state can be an incredibly effective argument.

But in order to advocate for the continued existence, much less support for the arts, we will need to introduce new ways of measuring the value of the arts. For arts advocates, our first step is to look carefully at the materials we are using and creating for the future. Which of them will be ineffective in a world where all jobs are scarce?

And what will we use to replace them?

Our second step is to begin thinking about engagement in arts and culture as an objective in itself rather than a step towards some other metric’s success. Arts, culture, design and craft are not good for people merely because they are good for business. “By making cultural flourishing part of the Wellbeing Economy, it has much greater potential to excite and engage societies in a movement towards a better future”: culture is both objective and means of achieving an economy based on human wellbeing.