A New and Unanticipated Vulnerability

Advocates for arts and culture have gradually become more comfortable and more knowledgeable in discussing the potential future effects of artificial intelligence on the creative industries. But our contributions to the field have largely been focused on issues of intellectual property infringement or the threat to artists’ and creatives’ jobs, with a side order of discussion on whether or not a synthetic form of intelligence can in fact create “real” art (and subsequently, what that means for the very definition of “art”.)

But we in the arts advocacy field currently risk a form of tunnel vision that leaves the arts vulnerable in ways we have not effectively anticipated.

Creativity Can't Be Siloed

We in the arts and culture sector – nonprofit organizations and arts institutions – have frequently been the first to champion more intersectional and equitable policies in the era of post-2020 upheaval, and we are quick to point out the societal benefits of the arts. But we too often continue to silo our sector as a “special interest group,” fighting for our piece of the funding pie.

Five years ago, if you had asked any of us which jobs could be taken over by robots or machine learning or neural networks, the vast majority of us would likely have listed those tasks that could be easily automated – mechanical labor, factory work, checkout lanes, and more. Very few of us expected our creative tasks, those we consider most “human,” to be the first to threaten our jobs. Now AI can not only pass the bar exam with higher accuracy than most aspiring lawyers, but also provide accessible, on-the-spot therapy appointments for those in need of mental health support. It can create artistic works that are mostly indistinguishable from those painted by master artists. It can write, direct, and animate entire films. It can produce new music from long-dead vocalists.

It's Not About Us

But at the end of the day, the story of artificial intelligence isn’t about us.

The more information comes to light about the proliferation of AI, the more it becomes clear that the arts are merely the canary in the AI coal mine.

Nearly ALL jobs are or will be at risk of being overtaken by AI in some form or another.

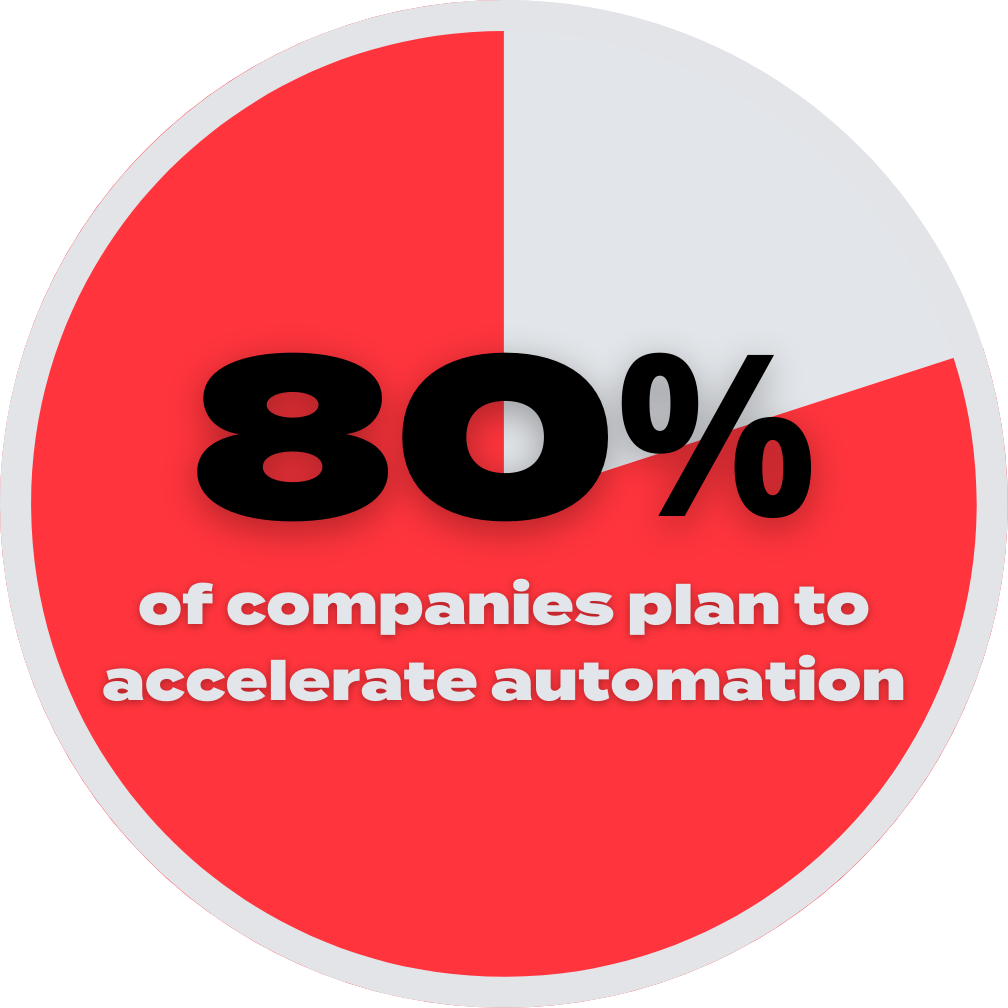

You read that right. In 2023, a little over one year ago, when ChatGPT 3.5 burst onto the scene, 59% of companies surveyed by the World Economic Forum – a combined 803 corporations representing over 11 million employees across 27 industries and 46 countries – saw developing and utilizing AI as a strategic priority. 80% of those companies planned to accelerate automation in their processes.

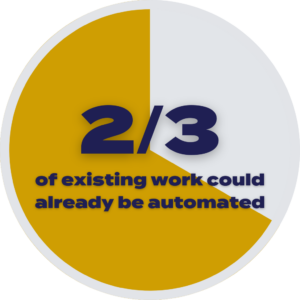

At the same time, an estimated two-thirds of occupations, across all industries, could already be automated to some extent by technologies already in existence, with employees estimating that AI could replace their labor on approximately a third of their work.

Just one example – in a recent Zoom meeting with arts advocates colleagues, it was pointed out that our use of Fireflies, an AI note-taking app, had effectively removed the need for us to appoint someone to the task of taking notes.

Just in the last year, 4,600 American workers have been laid off and replaced by AI. And those are only the ones we know about. Other companies have initiated hiring freezes, or cut staff ostensibly to lower costs, while investing the cost savings into AI technology.

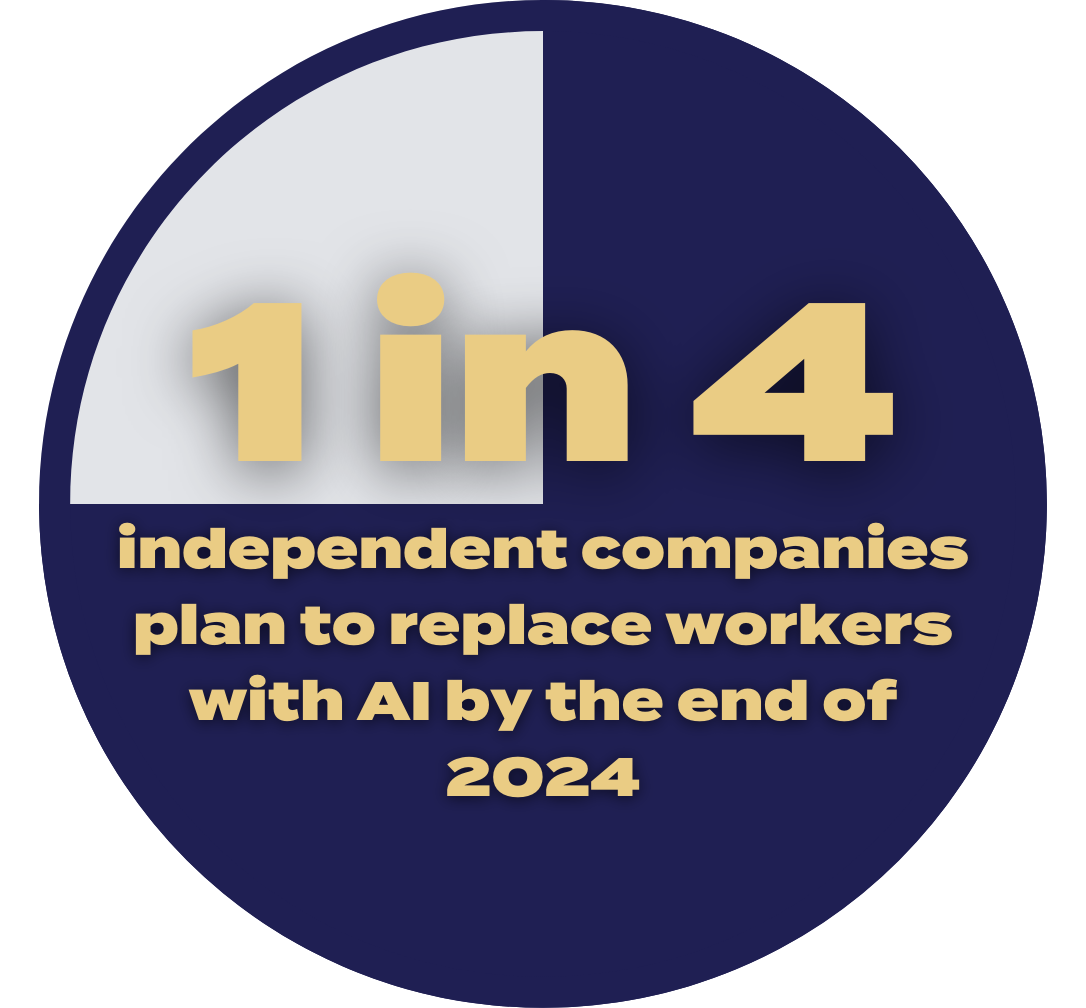

The rate of job loss is accelerating, and even modest estimates foresee immense workforce shifts. In August of 2023, Gallup found that 72% of Fortune 500 CEOs planned to replace at least some of their workforce with AI in the next 3 years. 16% intended to do so by the end of 2024.

But by January 2024, PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited), the second-largest network of independent firms in the world, estimated that nearly one in four, or 25% planned to replace workers with AI by the end of the year.

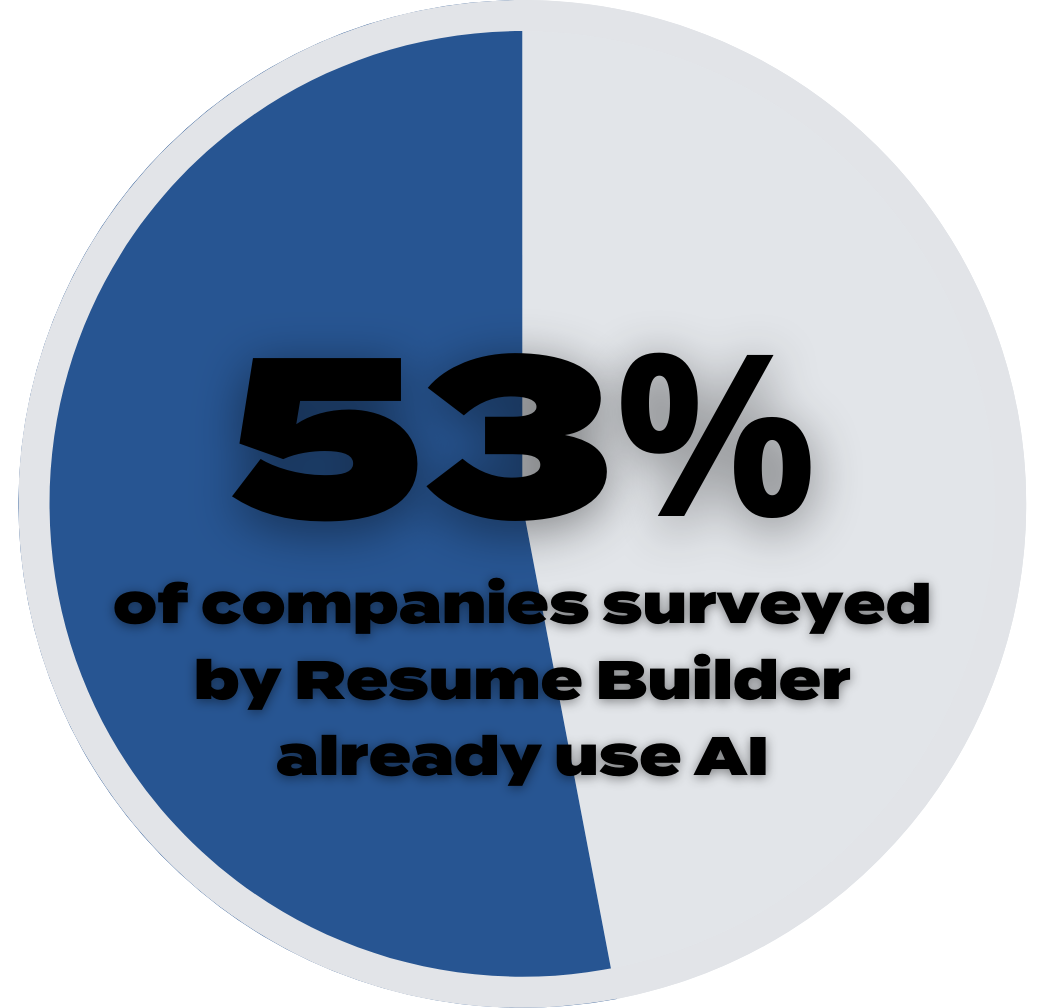

And Resume Builder found in November 2023 that over half of companies already use AI; 25% more will begin using it by the end of this year. 44% plan to lay off employees by the time New Year’s Day 2025 rolls around.

For arts advocates, the news may be decidedly worse; For businesses in media, entertainment, and sports, 90% plan to adopt AI tech in the near future.

Of course, for every doomsday fact about job loss due to AI, there can be found a chipper reassurance that AI will create large amounts of new jobs. But this is at best a temporary Band-Aid and at worst, a dose of reassuring flimflam. In fact, the World Economic Forum estimates that while as many as 69 million jobs could be created by 2027, 83 million jobs will be lost in the same period, a difference of 14 million jobs in the negative. This is a decidedly conservative estimate.

Saying the Quiet Part Aloud

This is not an accident, and we cannot pretend that the disruptions to come will resemble those of the past. While the growth of the internet, social media, smartphones, and many other technological innovations of the past 50 years have inarguably changed our lives in many ways, good and bad, none of them were designed with the intentional, purposeful goal of replacing one of the pillars of most of humanity’s, especially Americans’ lives: our work.

“By AGI, we mean highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work.”

OpenAI, the breakout leader of the AI space, defines AGI (artificial general intelligence) as “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work” (emphasis added).

Talk about “saying the quiet part out loud.”

What happens if the inventors of artificial intelligence meet their goals, and there are few jobs to be found in most industries, cities, or communities?

Reassessing Our Values

At this point, it is no longer a question of if artificial intelligence will dramatically affect our lives, but how.

All Americans have some deep thinking to do, but none more so than artists and the advocates who defend them.

At the end of the day, do we believe that creating and experiencing art are essential to a full life?

Or do we only think that art is meaningful or valuable if we’re selling that art or someone is profiting off of its sale?

If we believe that arts, culture, design, and craft have value beyond retail price (as I think we do,) we must begin defending art on more than economic or instrumental grounds. We must begin thinking about what it is that we as arts advocates are trying to preserve and propagate – the ability and right for every American and global citizen to access, engage with, and create art. Not because it makes us money, but because it makes us better.

Successfully meeting this challenge will not be easy. It will require the entire arts ecosystem to reconsider many of its long-standing assumptions about the value of art, face the risks in commoditizing it, and scrutinize its relationship with labor, well-being, and purpose.

Building a Better Future

At 4A Arts, we are building a framework to aid arts advocates in taking their next steps in an uncertain future, one that preserves art, champions it as a vital part of human lives, and utilizes it to imagine and develop a better future for all of us.

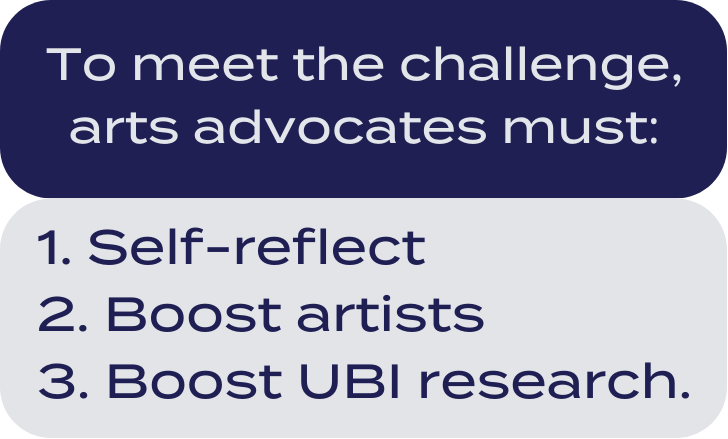

While discussion in this space must of necessity move quickly and adapt as needed in a rapidly changing environment, we believe that any effective movement to advocate for the arts in the age of artificial intelligence must begin with three pillars.

- First, arts advocates must analyze and reflect on the materials and positions they use to promote the value of the arts. Will any of them be effective in a world where all jobs are scarce, not just artists’?

- Second, it is imperative that we boost or fund artists and artistic projects focused on imagining and disseminating visions for optimistic new futures. Thankfully, the arts are uniquely positioned here; no other type of work is so tied to the very concept of imagination.

- Last (for now,) we must advocate for the funding of projects and initiatives that test and practice Universal Basic Income (UBI) or Universal Basic Services.

The proliferation of artificial intelligence rightly raises alarms. But it also provides an unprecedented opportunity. Never before has humanity been faced with the question of what it would do with itself, should work no longer consume much of our lives.

The arts ecosystem cannot afford to sit this conversation out, or limit our contribution to questions of intellectual property. Instead, we must remember that engaging in arts and culture has always been at the center of what it means to be human, and advocate for the right of all of us to participate in them.