4A Arts exists to change the narrative around arts and culture in the United States, particularly in this age facing an art vs. AI showdown. We believe art is for everyone, everyone is an artist, and American art creates American identity. We aim to lift up the work of artists (both professionals and passionate non-professionals) and to help inspire local, state, and national elected leaders to prioritize, support, and fund American arts and culture at levels commensurate with their impact on both the broader economy and our well-being.

For these reasons, we firmly stand on the side of human-generated creativity when debating art vs. AI and pondering “what is art?”

We know that American artists deserve to be supported and paid so that they (or we, as 4As believes every person is an artist) may continue to contribute to American culture, identity, entertainment, and thought.

What is art?

Throughout modern civilization, people (including us here at 4A Arts) have wondered “What is art?” and “What makes something art?” Our 4A Arts podcast’s title, Framing the Hammer, is based on a high school Socratic debate examining whether a simple hammer surrounded by a basic wooden frame could be considered art.

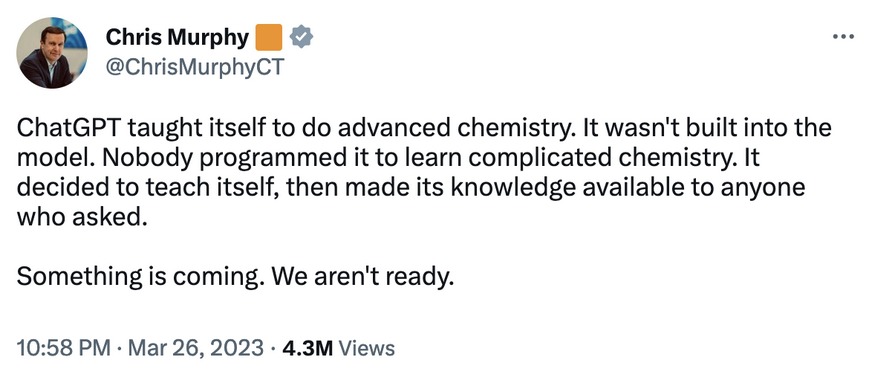

Theoretically, AI-generated “creativity” could replace human-generated creativity, be it written, painted, composed, or designed. But is it art if “it” is created by a machine and not a person?

As for the definition of “art”, some might argue along the lines of Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s test for obscenity in 1964: “I know it when I see it.” Does the same argument hold true for art – that we know it when we see it? (Whatever creative oeuvre the “it” might be…quiltwork, pottery, rapping?) Perhaps. But does that change if the work is generated through web-scraping to aggregate pre-existing ideas, formulas, and techniques?

Merriam-Webster defines art as the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects. Talk of art’s definition takes us perilously close to a rabbit hole of scenarios and arguments. Can we all agree with Merriam-Webster that imagination is necessary to create art and not just web crawling to re-compose 1’s and 0’s? Then again, what qualifies as imagination if AI can dream? With every question posed, we get closer and closer to issues of human rights, reality, responsibility, and the rapidly approaching consequences of not having adequately considered how to proceed.

Regardless of how one defines art, there is a reason we need to support creativity: the creative economy.

The Creative Economy

The “creative economy” encompasses not just painters and poets, but also art movers, poetry coffee shops, ushers, and mental health workers…all the forces of making artistic experience possible. Notably…these are all people. Arts and culture is an ecosystem that, when appropriately leveraged, brings innovative problem-solving human skills to all industries. Not only does the creative economy bring out the best in human creativity, it also employs people and allows them to pay for food and shelter, art supplies, and hopefully a vacation to recharge their batteries.

This creative economy, made up of imaginative people creating art that fosters American identity, is the second largest employer in the United States (after retail). These people number 4.9 million and contribute over $1 trillion to the GDP $877 billion to the GDP in 2021. For economic impact comparison, the creative economy generates more than agriculture and mining combined.

We might not know what should be done proactively yet to “deal” with AI. But we have already gotten a glimpse of AI-generated graphic design, pop music, illustration, and stories. With the exponential growth in capacity, it looks like the possibilities for AI-generated art could be endless. And with the speed of innovation and algorithmic ability to formulate whatever may appeal to the masses, robot-created art could become more popular than human-generated.

Is this the World We Want?

But surely it is safe to say we do not want mass lay-offs of TV writers, graphic designers, photographers, quilters, and architects in favor of AI replacements. And do we want to live in a world where dead or deep fake actors take the place of live actors? Or do we want AI to replace actual songwriters?

Our cultural ecosystem creates far more than just entertainment and enrichment. Arts and culture are also an overlooked economic engine for small towns, suburbs, and big cities alike. Replacement of human-generated art would devastate individuals and the profundity of the art we enjoy while decimating our economy.

We don’t know where AI will take us or what will happen in the art vs AI showdown. We can’t know if we face doomsday or a nothingburger. But we do know that now more than ever, our creative economy is critical to American business and deserves protection for long-term sustainability, with or without AI. Sadly, few U.S. studies exist that show the immense return on investment for arts and culture funding. But in the United Kingdom, recipients of Arts Council funding contributed an additional £2.35 billion to their national coffers–an estimated £5 for every £1 of taxpayer contributions to the arts. And in “The Loop” neighborhood in Chicago, for every dollar spent on a theater or concert ticket, $12 of revenue was generated for the Loop economy at large.

Immediate Solutions

Despite the many unknowns about arts vs AI, and the lack of cognizance about the issue on Capitol Hill, there are immediate steps elected leaders could take to shore up our creative economy and keep artists productive and employed. Notably, there is a raft of legislation introduced into Congress (though, coincidentally, none since mid-2022) collecting dust on the floors of both Congressional chambers. If Congress passed these bills, they would immediately help multiple sectors while demonstrating a bare minimum level of support for the people who help craft American identity.

Further, with more funding, the NEA could as an economic boost to small towns across the nation. To wit: in 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, 204 Chambers of Commerce from all fifty states signed a letter to Congress requesting a 600% increase in the NEA’s budget from $162.5 million in 2020 to $6 billion in 2021. These business leaders (who are generally fiscal conservative voters) know that cultural entities and artists help local economies thrive.

(And we can’t help point out that If $6 billion for the NEA seems like a lot, note that the Department of Defense budgeted $1.7 trillion toward mere development of the F-35 jet fighter, and that jet has yet to be built. To further illustrate, 2021 NEA appropriations – $167.5 million – comprised 0.0001% of discretionary spending. Meanwhile, defense spending was $742 billion, making up 46% of discretionary spending.)

Knowns and Unknowns

We can not know the extent to which AI will change our society, economy, or democracy. But we do know that art, artists, and artistic entities sustain communities and feed our human souls, our human passions, and our human imaginations with thought-provoking entertainment.

Before AI develops exponentially (in whatever unpredictable form that might take), it’s a great time to shore up our creative economy to preserve what brings great meaning to our lives: human imagination, human creativity, and human art.