How many of us, as children or otherwise, have gone on some outdoor adventure and brought home a rock or shell? Perhaps it was a stone of unusual smoothness, or a piece of quartz that sparkled, or a shell with a fluted pink inner curve. We carry them home and place them on a shelf as a souvenir of our travels, or perhaps keep them in our pockets and rub our thumbs against them like a worry-stone.

The Makapansgat cobble is a piece of smooth, reddish-colored jasperite a little over three inches in height that was found in 1925 in a cave in the Makapan Valley north of Mokopane, South Africa amongst the remains of several australopithecus africanus, an early hominid relative of modern-day homo sapiens. But two things make this pebble stand out: first, it bears the naturally-formed impressions of what appear to be hominid faces and second – and perhaps most significant – it was found at least three miles away from the nearest possible source of such a stone.

Internationally-renowned rock art expert Robert Bednarik, Chair Professor of the International Centre of Rock Art Dating at Hebei Normal University in Shijiazhuang, China examined the stone in 1997, and his examination found that the distinct faces found on it were entirely the result of natural processes rather than carving. He also notes that the cobble itself is unlikely to have been used as a tool since no other evidence of tool usage or creation by australopithecus exists, concluding that “…the object was collected by australopithecus for its visual qualities” (1998, p. 7).

In short, one day, sometime between 2.5 and three million years ago, a four-foot-tall ape-like creature walked on two legs into a cave in what is now South Africa carrying something that today “outshines the other treasures in the [British M]useum’s halls.”

The Makapansgat cobble is the oldest piece of “found art” in the world.

But what is it about this stone, approximately the size of a modern human’s palm, that makes it art? Why are we fascinated by its pits and indentations, and why did our hominid predecessor decide to pick it up and carry it so far away?

Until the early part of the twentieth century, the accepted definition of art included only those works deliberately created by human hands. But in 1917, Marcel Duchamp shocked the art world when he submitted Fountain for an exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at the Grand Central Palace in New York. Fountain, an upside-down porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt,” has earned the title “Most Influential Piece of Modern Art,” as voted on by a panel of 500 top art experts in 2004.

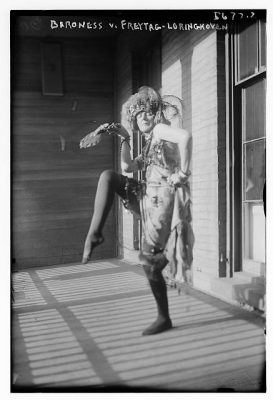

What was so shocking and world-altering about Fountain wasn’t just the subject matter – medieval and Renaissance literature from Chaucer to Bosch features the scatological on a regular basis, while it was such a trope in the Early Modern era that an entire book has been written on the subject – it was the idea that something which normally belonged in a department store or trash heap could be art simply by elevating it to such. Duchamp had been experimenting with found art, or what he called “ready-mades” since 1913, but it’s likely that Fountain was originally the work of artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, who was known for creating bras out of tin tomato cans and was likely the principal artist on the 1917 work God, a cast-iron plumbing trap mounted onto a miter box, previously attributed to artist Morton Livingston Schamberg. And in 1913, on her way to her wedding, she picked up a four-inch wide rusted ring off the street and named it Enduring Ornament, much like our australopithecus friend.

Von Freytag-Loringhoven, Duchamp, and other artists in the Dada movement had brought to light the idea that art is not just an object created specifically for aesthetic purposes, but instead we find the aesthetic everywhere we go. Andy Warhol would later expand on the idea when, inspired by his own daily consumption habits (“I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again,”) created 32 silkscreened canvases illustrated with Campbell’s Soup cans, a grocery-store staple.

Unlike his contemporary, Roy Lichtenstein, who deliberately set out to question the bounds of art (“It brings up the question ‘What is art?’”, Lichtenstein said in 1962,) Warhol claimed “I just paint things I always thought were beautiful, things you use every day and never think about…I just do it because I like it” (Time, 1962).

At this first exhibition, despite indifference from the public, Campbell’s Soup Cans caused a sensation in the art world. The debate about how art could concern itself with something so everyday, and seem to mimic commercial mass production, ensured that the paintings received plenty of attention. An art dealer in a nearby gallery even sold actual soup cans by way of criticism, advertising them as cheaper than Warhol’s. (Martin Dean for Sotheby’s, 2018).

What could be more everyday than a little rock with a face on it, or a series of soup cans? A small hominid carried the Makapansgat cobble into a cave, three million years ago, while Warhol’s complete Soup Cans sold to New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1996 for $15 million.

Warhol’s work, of course, is not as simple as it appears on its surface, with “the artist’s handiwork…evident through the slight variations in the lettering and in the hand-stamped fluer-de-lis symbols on the bottom of each can,” and “subtle differences and imperfections, meaning that this really was ‘high’ art dwelling on a ‘low’.“ And yet despite its designation as “high” art, a quick search on Amazon.com reveals 260 pieces of merchandise based on the work, including an unframed print for just $9.97 and a blind box collection of mini Warhol artworks packaged in the iconic soup cans.

Is bringing a stone home to a cave so much different from having a mid-twentieth century icon shipped to our front door?

But what differentiates the Makapansgat cobble and Warhol’s Soup Cans from just any other stone, or the Campbell’s Soup cans at one’s local supermarket?

To do that, a definition of art has been suggested, by the New York Times and art scholar Douglas Rosenberg, chair of the University of Wisconsin Madison Art Department, as “a form that exceeds use.”

If we take this definition, we must reconsider our everyday surroundings and think about how many times we choose an object or feature, not just because of its function, but because we like the way it looks. We carry home shells from the seashore to remind us of our vacation, but we choose those that are unique, smooth, or beautiful to our eyes in some way in the same way that we continue to add retro styling to 2022 vehicles. (A review of the 2022 Ford Mustang, one of the U.S.’s most quintessential muscle cars, refers to its throwback styling as “assertive” and “sinister,” firmly establishing the automotive enthusiast’s desire for features that communicate more than just its standard 310 hp or improvements in fuel economy.)

Where else in our lives might we be surrounded by the mundane which, on second thought, is a world carefully crafted for our own aesthetic likes and dislikes? How many times have we chosen an item just because we, like Warhol, simply like it?

When we begin to consider our surroundings with that lens, we discover a world where art is embedded into every nook and cranny. In fact, when Americans were surveyed about whether they attended an arts or cultural event in the previous year, but were only given traditional arts events (zoos, musical performances, museums, etc.), 72% reported having attended. But when that definition was expanded to include other places they might have experienced art, such as public parks, schools, airports, or even shopping malls, that number rose to 77% (Americans for the Arts, 2018, p. 14-15).

What if we considered the aesthetic value brought to our lives by the landscapers that beautify our front walkways, the hairdresser who paints new highlights or applies braids into our hair, or choosing a cat tree for our favorite furry feline, rather than just their use?

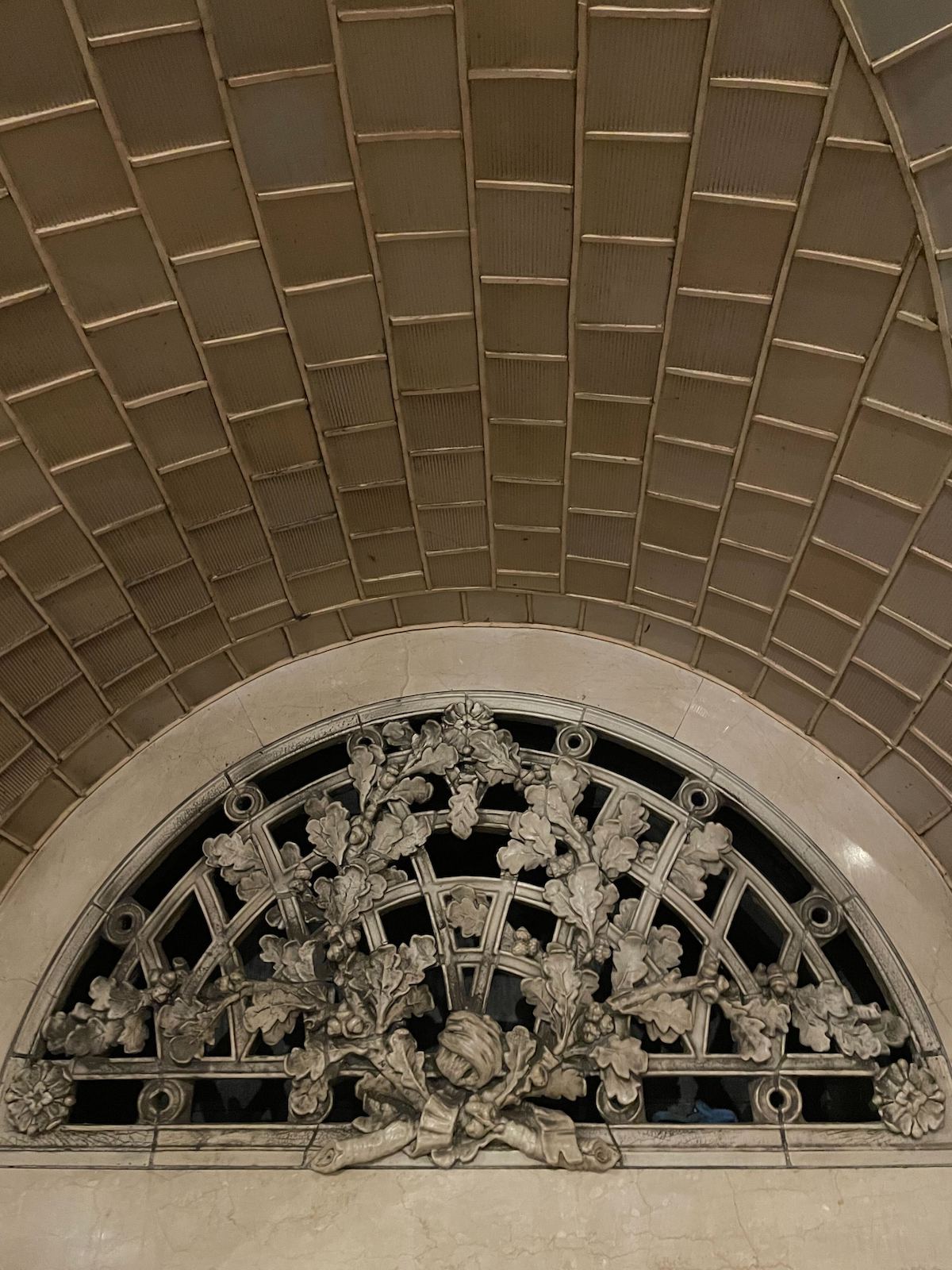

After all, there was a time when architects ensured that even our everyday commute was beautified, giving ordinary Americans access to the same art neouveau or Greek Revival touches as those who donated thousands to the country’s greatest museums. What kind of country could we become if we once again took the time to beautify our lives, consciously and purposefully?