Here at 4A Arts, we frequently emphasize the way art strengthens communities. It creates ties that bind, helps people push past vulnerabilities, cures loneliness, helps us demonstrate self-expression, dismantles facades, and (some might say most importantly) entertains us.

And so does sport.

Arts & Sports Struggle in different ways

Dozens of countries have a Ministry of Culture that lump together arts and sports. (Wouldn’t it be nice if the United States were on that list in some form?) When combining arts and athletics in federal departments, arts advocates would say that sports don’t need a boost, but the arts do. Sure, they both foster everything listed in the paragraph above, but in the United States, at least, in 2024, we all know sports are not struggling for participants, lessons, ticket-buyers, spectators and societal support. Meanwhile, the arts are in freefall. (But that’s another topic for another day.)

Art was part of olympic ideal

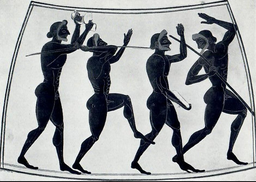

Nevertheless, art and athletics have been partnered dating back to ancient Greece when the Olympics included art in the pursuit of excellence in both mind and body.

Aside from foot races and javelin-throwing, the ancient games held competitions in multiple artistic pursuit, most regularly trumpeting and heralding. There were also occasional competitions in other disciplines, such as comedy, tragedy, lyre, lute, and aulos (a woodwind instrument).

Of course there’s the angle of art documenting the Olympics in the form of coins, mosaics, painting, pottery, and sculpture. These elements of human creativity leave us countless and priceless treasures serving as our primary sources of historic Olympic records.

Art was meant to be in modern games

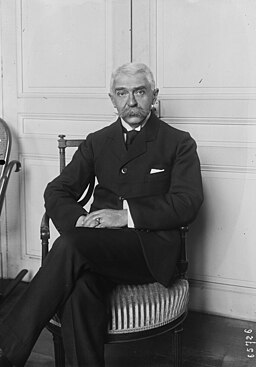

By the time we arrived at the first modern Olympics (which first took place in 1896), the founder of the International Olympic Committee, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, explicitly advocated for including the arts. Coubertin believed the games and the participants were both athletes and artists combining, as he stated it, “mark [the] intimate relation that we want to better maintain between muscle and mind.”

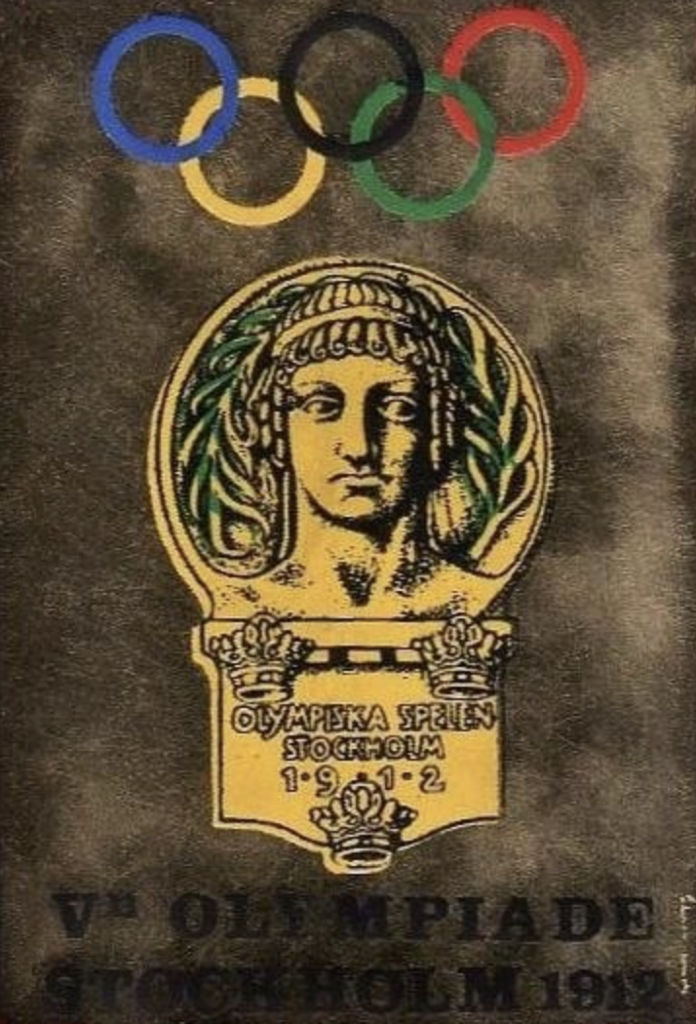

By the 1912 Olympics held in Stockholm, Sweden, Coubertin realized his vision when arts were included for the first time, with the caveat that artworks must be inspired by athletics and athletes. The competitions included architecture, music, painting, sculpture, and literature. Thirty-five works were submitted while five gold and two silver medals were distributed. (Records indicate “no award given” for sculpture, designs for town planning, painting, literature and music.)

Of note, the gold winning medalist(s) of 1912 in the literature category were George Hohrod and Martin Eschbach for their work, Ode to Sport. But in fact, “Hohrod and Eschbach” were merely pseudonym Coubertin used for his own work.

Modern Olympics Hosted multiple art competitions

The five artistic categories endured through the 1920 games in ravaged post-war Belgium (though mostly as an after-thought) and in 1924 Paris (where the Soviets won several medals despite sending no athletes because they considered the Games a “bourgeois” festival).

Judgment and scoring of the artworks were always a dilemma, due to confusing and difficult criteria. For example, despite there being categories for “orchestral,” “instrumental,” and “solo/chorus,” there were no actual musical performances. Instead, the competition rested on the submission and reading of paper scores.

Change came in 1928 Amsterdam, when artists were allowed to sell their works, slightly undercutting the rule that Olympians should always be amateurs. Ultimately, by 1948, it was determined that all of the artists submitting work were essentially “professionals”, leading to the argument from artistic naysayers that arts didn’t belong in the Olympic as competitive events at all.

Shifting to the Cultural Olympiad

Since 1956, a cornerstone of hosting the Olympics has been the Cultural Olympiad which has experienced wildly various levels of participation and investment (and sometimes lack thereof) over the decades.

"Peace Camp," a part of the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad in which several venues hosted poetry readings and glowing orbs filled various sites around the U.K. Courtesy: Robin Leicester, Wikimedia Commons.

Paris has embraced its artistic history in hosting the 2024 Olympics by going all out for this year’s Cultural Olympiad, featuring events throughout the city and the country at large before, during, and after the games. For example, a central Parisian concert venue named “Olympia” hosted a variety of events leading up to the opening ceremony, including film screenings, acrobatics, and live illustration competitions. Meanwhile, endless exhibitions, from equine paintings at the Palace of Versailles, to athletic fashion shows in Lille, to the fêting of vintage Olympic posters Gagosian, and even to the exhibition of questionably-acquired ancient pottery at the Louvre.

Finally, there is a specifically constructed Olympic Museum in Paris providing an immersive 365 degree viewing of the sites of Paris and the Olympic sites set to thrilling music plus 37 artworks by previous Olympians will be on display. In short, the entirety of Parisian cultural institutions is getting in on the game(s).

While the pursuit of faster, higher, stronger undoubtedly focuses on the track, the pool, the lakes, the court, and the fields; eventually we all need a moment to reflect, to think, to rest. Our bodies eventually tire, but our spirit and minds expand and deepen. The Olympics thrill us by bringing together the spirit of camaraderie and competition in peace. It breaks down barriers and reveals our humanity.

Just like art.

Expressing the JOY of the games

Perhaps Olympism might catalyze our society to prioritize art along with sport, and give it the support it deserves to heal our spirits after our bodies are depleted – and not just with a Taylor Swift appearance at the Los Angeles opening ceremony in 2028. Like the training grounds of youth sports in pools, gyms, and on fields, let’s also foster artistic expression and participation not only in childhood, but perhaps more importantly for adults and seniors. Let’s meld muscle and mind as Coubertin originally envisioned.

Finally, cable provider Comcast has aired a commercial relentlessly during their Olympic broadcast, calling their campaign “Joy of the Games.” The ad is full of athletes, children, and spectators reveling in the joy of the Olympics. How do they express that joy? – through dance. They are dancing for the cameras, in the stands, on the fields, on social media. And isn’t the natural expression of joy, found so often in artistic expression, worthy of the same support we give athletics?