The Observer Effect

Nobel prize winning physicist Erwin Schrödinger is perhaps most famous in popular culture for his thought experiment based on a cat in a box. In the experiment, until the box is opened to check, the cat is both alive AND dead. (Confused? Here’s some help.)

For Schrödinger’s cat, its fate is suspended until the moment of measurement. The “observer effect” in quantum mechanics explains how subatomic particles only “decide” how they will behave at the moment of measurement; our very reality is dependent upon whether or not we choose to consciously weigh in on it.

Tools and Traditions

In a September, 2022 interview with the New York Times, artist and tabletop game designer Jason M. Allen told journalist Kevin Roose that “Art is dead, dude. It’s over. A.I. won. Humans lost.” The outrage from the art community was predictable.

Out of context, Allen’s remark appears combative and inflammatory, practically tailor-made to antagonize artists who work in traditional mediums and those who support them. The problem is, Allen never intended to imply that art is in fact, dead, or that artists are inherently Luddites attempting to save the horse and buggy in the face of metaphorical oncoming auto traffic.

When we spoke to Allen in a private interview in July, he clarified his statement: “[I]f this is an artwork and if I’m not an artist, then art is dead…This is a tool and that’s my argument with the United States Copyright Office…[P]lease point out to me how this image was manifested or brought out of the lack of human authorship and they cannot.”

TL;DR — Someone entered an art competition with an AI-generated piece and won the first prize.

— Genel Jumalon ✈️ Anime Ink + Planet Anime (@GenelJumalon) August 30, 2022

Yeah that's pretty fucking shitty. pic.twitter.com/vjn1IdJcsL

In August, we chatted with Allen again on our podcast, Framing the Hammer, and he was less sanguine: “Contemporary art, rather than challenging the status quo, has become complicit with the system of control, becoming another commodity and losing its critical edge.”

“I Yearn for the Past…”

Allen is hardly alone in his disdain for the status of contemporary art. From Instagram accounts bearing the ID “modern_art_sucks” and Reddit threads to an entire museum dedicated to bad art, complaints about contemporary art’s dearth of value date back to the Middle Ages. Yoshida Kenkō denounced the taste of his own thirteenth century Japan: “I yearn for the past. Modern fashions seem to keep on growing more and more debased…even among the splendid pieces of furniture built by our master cabinetmakers, those in the old forms are the most pleasing. And as for writing letters, surviving scraps from the past reveal how superb the phrasing used to be…”

Even Plato recommended banishing dramatic poetry from his Republic and opined that “if [an artist] truly had knowledge of the things he imitates, he’d be much more serious about actions than about imitations of them…”

When leading American art critic Dave Hickey hung up his hat and resigned in 2012, he did so thumbing his nose at the art world: “What can I tell you? It’s nasty and it’s stupid.”

(Hickey may have had a point: the growing use of freeports to stash art away in secrecy for decades in order to cash in on its later value has a particularly nasty effect on new art: director of the Broad Museum of contemporary art in Los Angeles Joanne Heyler described to the New York Times how the practice puts art “intellectually almost in a coma.”)

AI-generated art has run smack into similar reproofs. The exponential growth of AI-fueled diffusion models – a form of AI image generation that works by first adding visual “noise” to images and then removing it (counter-intuitive, I know) – has, of course, opened itself up to the critiques of those who claim that “every image a generative tool produces ‘is an infringing, derivative work’” with a “general sugary, candy look…It looks pretty, but it tastes terrible.”

Plagiarism and MS Paint

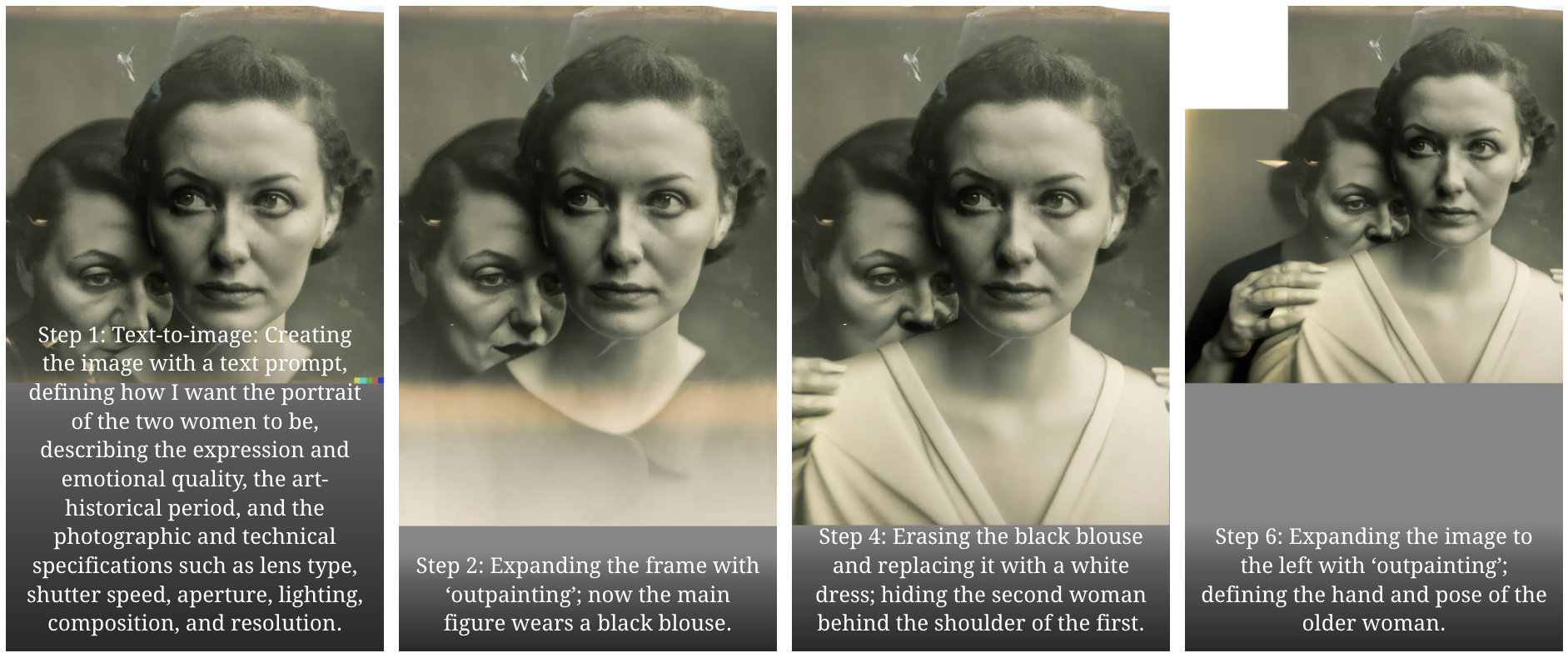

But is it fair to artists like Allen, or to German photographer and artist Boris Eldagsen (who won the 2023 Sony World Photography Award for his work, The Electrician,) to assert that the hours they put into crafting their award-winning works amounts to nothing more than plagiarism?

Allen claims he spent more than 80 hours prompting, crafting, and regenerating Théâtre D’opéra Spatial. Eldagsen drew on his experience as a university professor to explain some of the twenty different stages of prompting in DALL-E, going so far as to provide images of the progress of the work.

In my curiosity, I made a few stabs at prompting for myself, and quickly found that creating anything that truly resembles “art” is not so easy as it seems, nor is it simply “a 21st-century collage tool,” as attorney Matthew Butterick claims.

For my last commentary on AI, I attempted to create an illustration of the metaphor at the essay’s heart, which was about finding our way through the complicated and murky landscape of AI art. I played around with several free AI tools, including Nightcafe, Craiyon, Adobe Firefly, and Canva’s native “Magic Media” tool. The results were not exactly breathtaking, much less inspiring.

When compared to Théâtre D’opéra Spatial or The Electrician, one thing quickly becomes clear: prompting a diffusion model is not as easy as just throwing a few words at an AI image generator, and out pops a masterpiece worthy of the Rijksmuseum. I tried every combination of words I could think of in order to create something resembling a photo of a dark forest, with a path that splits into two, something like an eerie version of the end of Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken.” But try as I might, the results reminded me less of classic poetry and more like the way I felt tooling around with MS Paint in my high school computer lab, circa 1998.

It’s a far cry from the way artist and illustrator Molly Crabapple described the technology to Doha Debates: “The only reason any AI generator is good is because it was trained on billions and billions of stolen images…The products are good enough to spit out a somewhat soulless facsimile of the work of any artist that they’re trained on.”

The Cat's Out of the...Box?

That’s not to say that Crabapple doesn’t bring up important points about the ways that AI may negatively impact the ability of artists to make a living from their work, or the charges that AI companies use artists’ work without their consent in order to train the models. The difficulty in parsing out who owns what and where fair use ends is clear when Allen, a staunch defender of the technology, describes to Crabapple and host Joshua Johnson his current struggles to register Théâtre D’opéra Spatial with the U.S. Copyright Office. “I’m now being faced with the challenge of how I am going to share my work, knowing that anybody can take it and use it however they want.”

Is it possible for AI to churn out objectively terrible, “soulless” work? Absolutely. Not to mention the occasional uncanny errors that leave audiences feeling a bit…unnerved. Just take a look at this series of AI-generated images using the simple prompt “cat in a box.”

But it is disingenuous to state that art created using AI generation isn’t art. After all, it’s not like our medieval forebears were automatically experts in the art of cat illustration, simply by virtue of using paint and pigment.

However, while AI visual art may need more attention to detailed prompting and multiple iterations, AI video generation has become shockingly polished, with little indication of its “artificial” origins.

To test out the waters of AI video creation, I first tried out South Korean startup Deepbrain AI, which bills its AI Studios as “a text-to-video creation platform that integrates powerful LLMs and AI avatars to produce videos without the need for cameras, microphones, or actors.” In order to better assess the video quality, I picked a topic I’m closely familiar with: the creative economy. Its free templates are limited, so I ended up with a background themed to a company cafeteria (Hey, food is culture!) I prompted it by asking one single, simple question: “What are the effects of arts and culture on a country’s economy?”

That’s it. No other information or data was provided. It gave me this, and of course now I am feeling much like those artists who fear for their own jobs:

Deepbrain’s initial foray into analyzing the creative economy seemed a bit surface-level to me, though, so next I moved over to another free AI video generator, invideo AI. It offers a bit more detail in its prompting process, so I started with “Create a YouTube explainer video about the creative economy and how much arts and culture contribute to a country’s economy.” Invideo then gave me options for target audience, style, and platform; I chose “policy makers,” “inspiring” and “YouTube.”

Again, that’s it. I provided no information, no data, no images or script.

The results are staggering.

“Nollywood” is a real thing, by the way – proof positive that AI can find accurate examples that range far afield from a researcher’s usual catalog.

But would I consider myself the “director” or “producer” of either video? Hardly. I felt more artistic ownership over this embarrassingly disproportionate calico.

AI may have finally figured out how to draw hands, but paws remain out of its reach. (This gem came from Canva.)

A Cat Named Pandora

It’s easy to see why anxieties run high. If a machine can create the kind of video in seconds that took an entire team several weeks to produce, will those who rely on their creative skills find room in an increasingly crowded workforce? And if AI is so terribly bad at drawing cats, but it can work exponentially more cheaply than a human artist, will that lead to awkward felines everywhere as companies prioritize profit over quality or aesthetics?

The truth is, we don’t yet know. Schrödinger’s AI is still in the box. Is art dead? Will AI detonate a nuclear bomb into the heart of human creativity?

It is impossible to know until we open the box fully. But the act of “opening the box” and discovering how exactly AI is going to affect society will inevitably influence those exact impacts. Whether we seek to limit AI’s growth for fear of its outcomes, use it to expand our creativity and make our increasingly stressful lives easier, or sit back and let large corporations decide for us, our lives will permanently be altered. But just like in the observer effect, how we react to AI’s growth in these very early stages has the ability to set its future course.

At the risk of inflicting more physics lessons, learning about AI has become, for me, like some sort of Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. The more I learn about the topic, the more I am convinced that AI art generation is a tool, not an enemy. But it is an astonishingly powerful tool, and one that has the power to forever change the way we value the creative process and its products. The closer we look at what it can do – for good or for ill – the more we lose track of what it could do.

If you upgrade to Nightcafe's newest model, SDXL 1.0, the results start looking eerily realistic.

Here at 4A Arts, we take very seriously the rights of artists and the importance of the creative economy and the arts workers who make up its backbone. Our staff consists of dedicated arts advocates from the team who successfully lobbied the U.S. House of Representatives for a first-of-its-kind hearing on the importance of the creative economy and brought you Ovation’s The Green Room with Nadia Brown, the founder and artistic director of FringeNYC, and a development professional with nearly twenty years of experience in the arts, from Jazz at Lincoln Center to Actors Theatre of Louisville.

We believe that arts and culture are basic human rights and powerful tools for building a whole and healthy society, and that it will take robust support from government and private funders to ensure that America’s arts and culture continue not only to survive, but thrive in a future where creativity and innovation become ever more vital.

Hotpot is an AI art generator that offers users a chance to choose a style of art. I rather like this little pop art kitten.

But are we asking the right questions, and measuring the most important aspects of an artist’s life? Or can we envision a future where AI frees us all to be more creative, more expressive, and more human?

For Jason M. Allen, art is certainly not dead. For him, AI art “is the most powerful form of human freedom of expression that’s ever been created, well then maybe it’s you that are anti-art. Maybe you’re the reason that art is dying, not me.”