I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.

The Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration is a practical relief project which also emphasizes the best tradition of the democratic spirit.

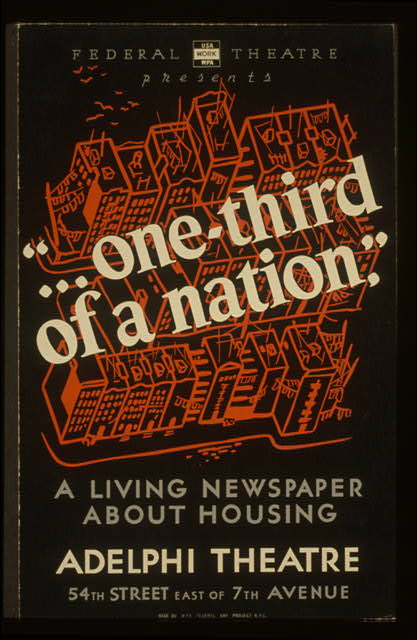

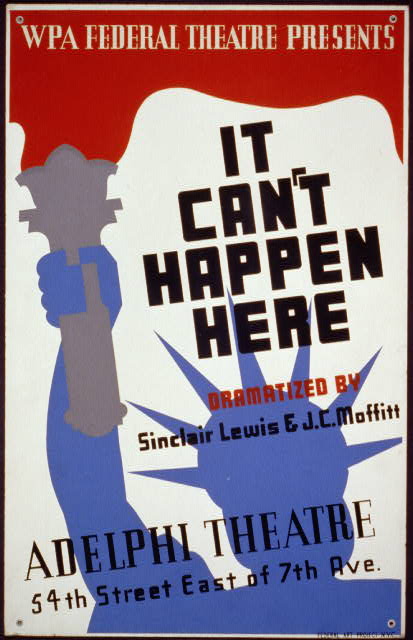

A brief history: as an attempt to address both the basic needs of artists and to promote a unifying theme around democracy in order to counteract rising totalitarianism abroad as war clouds gathered in Europe and Asia, $27 million dollars was approved in 1935, (over half a billion dollars in 2022 valuation), under the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA’s) Federal Project Number One (Federal One). The project was divided into five groups: The Federal Art Project, The Federal Music Project, The Federal Theatre Project, The Federal Writers’ Project, and The Historical Records Survey (originally part of the Federal Writers’ Project).

Federal One had two main principles:

- That in time of need the artist, no less than the manual worker, is entitled to employment as an artist at the public expense and;

- That the arts, no less than business, agriculture, and labor, are and should be the immediate concern of the ideal commonwealth.

It is worth noting that at a time of horrific bigotry of all forms, all projects were supposed to operate without discrimination regarding race, creed, color, religion, or political affiliation. Such progressive outlooks were in keeping with the nation’s founding principles of the French Enlightenment and were, in and of themselves, mileposts pointing toward the Civil Rights movements ahead in the decades following WWII.

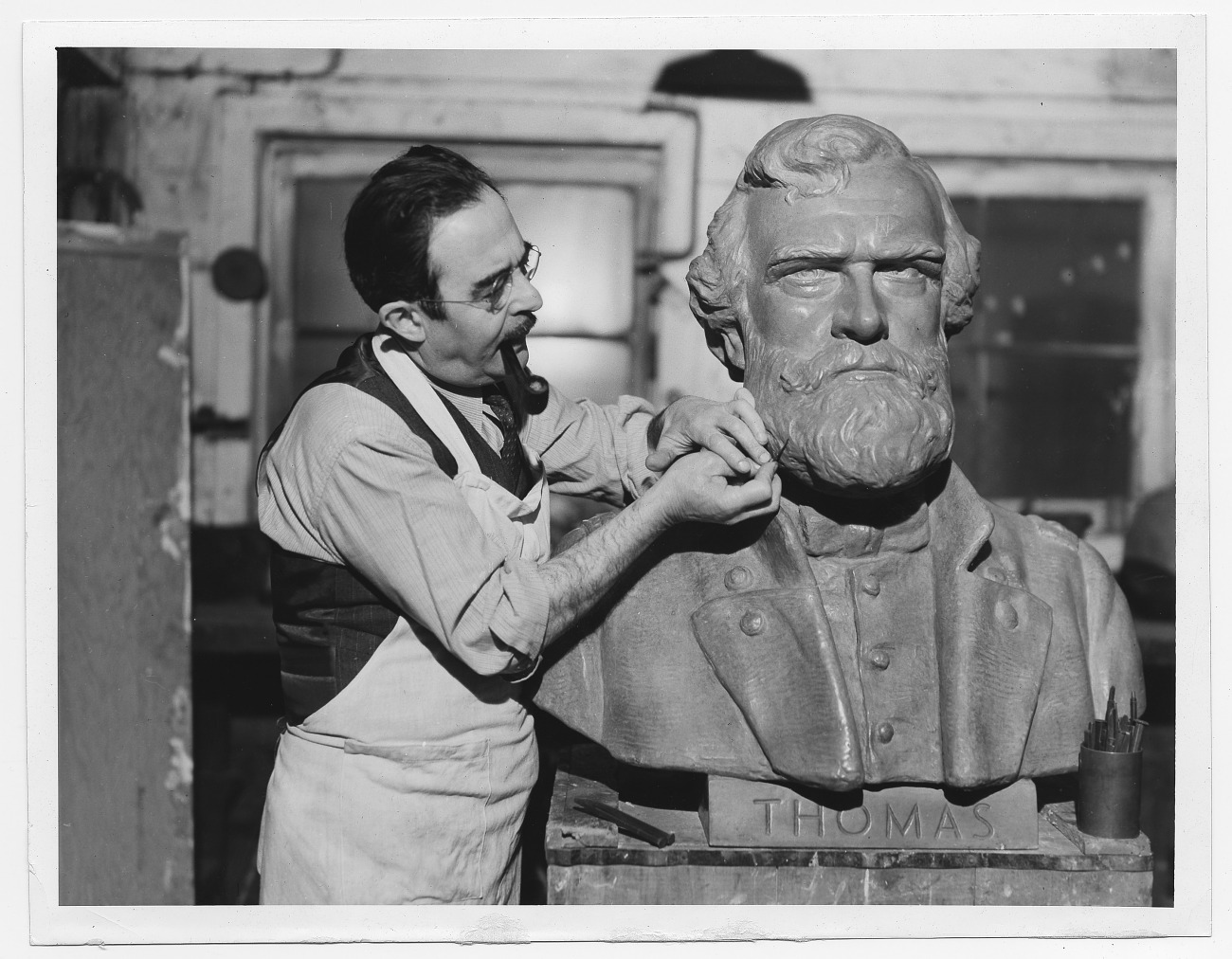

With key champions like Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, at its peak Federal One employed some 40,000 writers, musicians, artists, and actors. According to the Washington State Project, based out of the University of Washington, The Federal Art Project alone produced over 2,500 murals, 108,000 paintings, 17,700 sculptures, 11,200 print designs, and 35,000 posters for the Index of American Design along with innumerable other objects of craft: “Artists supported by the FAP were active in a wide variety of areas, including traditional pursuits, like easel painting, as well as more novel (for the era) fields like community education and the documentation of folk art” (Mahoney, Washington State Project).

The Federal Writers’ Project employed many authors known and read today, such as John Steinbeck and Zora Neale Hurston. Steinbeck himself was known for poring over the contents of one of the 48 WPA guides, calling them “the most comprehensive account of the United States ever got together … compiled… by the best writers in America” (PBS.) Hurston’s essay, “Turpentine,” is still considered the authoritative work on turpentine camps in Florida to this day.

While some elements like the Federal Writers’ Project continued until 1943, under pressure from Congress, Federal One ended in 1939 after four years in operation. Congress cited complaints from both sides of the political spectrum. From the Left came cries of censorship from actors in the Theatre Project. From the Right, complaints from what would later become the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC,) that the program had become infiltrated and influenced by “communists.” Even with that ending, the noble impulses of Federal One continue to this day in the form of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The power and the promise of the art generated under the auspices of the Federal Art Project are with us as icons to this day. From Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother to the nascent modernist stylings of a young Jackson Pollock, the artists of the Federal Art Project and the other projects grouped under the WPA’s Federal One effort fanned out across a Depression-ravaged America and sought to make sense of both her origins and her promise in the face of a world gone mad with rising authoritarianism.

Art, then as now, is simultaneously meal and recipe, compass and map, sword and shield. We know this to be true on a level so deeply rooted in our individual and shared psyches that it is often lost in our subconscious, becoming the background to our lives in the form of the movies we enjoy, the concerts we attend, the books that act as the best of friends, and the fine arts that inspire us to see, as Abraham Lincoln’s Inaugural Address would highlight, the very “…better angels of our nature(s).”