What do we mean when we use the word “art?” When we see or speak the word, a variety of images likely come to mind, from art galleries to paint palettes to the Mona Lisa.

Or perhaps your experiences include the performing arts, with audiences clapping to final bows, or the literary ones, with stacks of novels piled up beside rainy windows and steaming cups of your preferred hot beverage (or perhaps that’s just me).

But regardless, unless it’s a topic that you deliberately think about, “the arts” typically bring to mind one of seven different forms or genres most often taught as the seven forms in a beginner arts class: painting, sculpture, literature, architecture, theater, cinema, and music.

But there is more to the arts than textbook classifications. As it turns out, the definition of “art” is a slippery thing.

Our English word, art, and its translation in the Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian, and a host of other regional languages) are descendants of the Latin root word, arte, meaning “skill.” (Fun fact: Spanish always capitalizes the word in a nod to its importance, Arte. Nice to see SOMEONE give art Arte its due).

An artist, in Latin, is an artifex. But then so is a craftsman (a craftswoman, and thereby a female artist, is an artificis; the Romans were, of course, rather picky about their gendered nouns. We at 4A Arts encourage everyone to choose the noun or pronoun that fits them best).

In fact, despite the “High” Renaissance’s reputation for churning out some of the biggest name artists in the ‘biz – from 1490 to 1530, Europe saw the career heights of Michelangelo, Da Vinci, Raphael, Bramante, and Titian – but it wasn’t until over a century later, in the 1610s, that the word art would begin to take on the meaning it has today, that of works of creative skill, beauty, and imagination, created by an individual artist of great skill and training. The artists who adorned sixteenth century Italy with their works would have instead been known as “craftsmen.”

Facade of Amiens Cathedral featuring rural occupations. Courtesy HaguardDuNord under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.

Prior to that, in the Western World, the word art would have referred more to the skills one learned via training or scholarship, and particularly to the seven liberal arts originally established in ancient Greece: the quadrivium (astronomy, mathematics, geometry, and music,) later followed by the addition of the trivium (rhetoric, grammar, and logic, which form our modern basis of writing and persuasion.) During the European Middle Ages, the first public schools, which were based on a foundation of the liberal arts, sprung up in the cathedrals and churches that were literally being built right around the students by the very same types of anonymous skilled workers that would go on to international celebrity status just a few hundred years later.

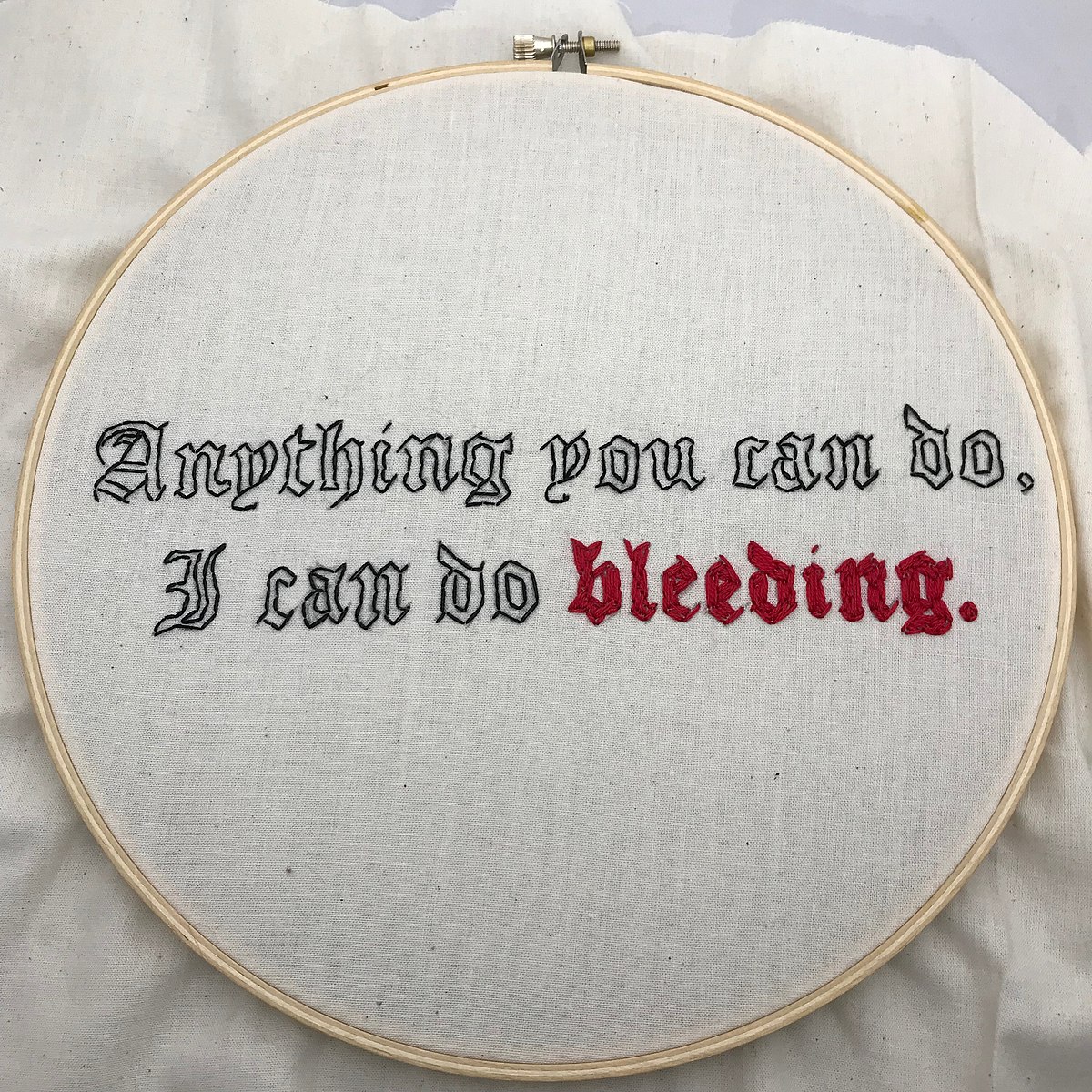

So what is craft, then? Today, whole chain stores are devoted to crafting, from Michael’s to Joann Fabrics to Artist & Craftsman Supply.

If art refers to skill or training, can studying the etymology of craft give us any insight into the nature of art? As it turns out…maybe not.

The word craft descends from Old English cræft or High German chraft, meaning “power, physical strength, might,” and – there’s that word again – “skill.”

(Anyone denigrating the ladies in the local embroidery aisle might want to rethink their image of crafters).

But what if we turn to other languages? Do any of them imply snobby and untouchable? Do they place velvet ropes around the Metropolitan Museum of Art, test your knowledge of Shakespeare in the Park, or require white gloves and a cane for a stroll through Faulkner’s Oxford, Mississippi?

Decidedly not.

The Germanic languages use the word kunst for art, meaning “knowledge,” and again, “skill.” And in fact, kunst is derived from the same word we know in English as cunning; one can see the connection to “crafty” if you look carefully. It’s also the same root word as can, reflecting the inherent possibilities within any form of making.

Hebrew implies a relationship between the work and the education of the worker – the Hebrew word for art, אומנות, means “craftsmanship,” but also “fosterage,” and “tutorship.”

In Greek, we see the same connection – τέχνη refers to “craft, skill, or trade,” but also “cunning or wile,” and also the more subtle “means,” as in “the method or course of action used to achieve a result,” suggesting that the art is in the creating, not in the final product.

For the Hindi, it’s कला, or “prowess” and “skill.” (It also refers to a “membrane,” suggesting how art can act as a skin that covers or changes an appearance.) In Mongolian, урлаг is “art and craft,” but also “proficiency;” in Pashto, هنر (huner) refers not only to “art” and “talent” but also to “science and knowledge.”

But my favorite word and definition for art must be that of the Hawai’ians, where hana noʻeau refers to “the skillful work.”

The Hawai’ians acknowledge that the best art, of course, is done well. But it is no less work despite being art. And work requires practice, knowledge, and skill. The wonderful thing about skills and knowledge is that they can be learned, and that no definition of the word art – ancient or modern – refers to natural talent as a prerequisite for creating it. “Art,” in fact, appears to be the simple act of using one’s skill – however developed or amateur it may be – to create.